By Dionne Searcey, John Eligon and Farah Stockman, New York Times–

In an abrupt change of course, the mayor of New York vowed to cut the budget of the nation’s largest police force. In Los Angeles, the mayor called for redirecting millions of dollars from policing after protesters gathered outside his home. And in Minneapolis, City Council members pledged to dismantle their police force and completely reinvent how public safety is handled.

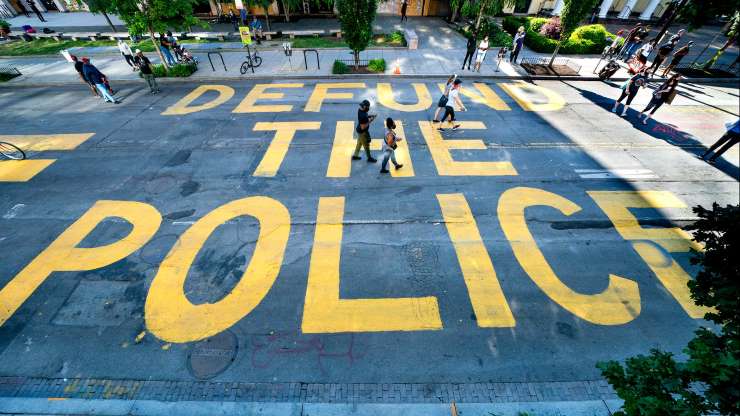

As tens of thousands of people have demonstrated against police violence over the past two weeks, calls have emerged in cities across the country for fundamental changes to American policing.

The pleas for change have taken a variety of forms — including measures to restrict police use of military-style equipment and efforts to require officers to face strict discipline in cases of misconduct. Parks, universities and schools have distanced themselves from local police departments, severing contracts. In some places, the calls for change have gone still further, aiming to abolish police departments, shift police funds into social services or defund police departments partly or entirely.

“It is a critical time that we can see concrete change,” said the Rev. Al Sharpton, who last week addressed the crowd gathered for a memorial service for George Floyd, the black man who died after a white police officer pressed his knee into his neck for nearly nine minutes in Minneapolis last month. “The legislation and the policy changes will be the ones that determine the victory of this movement.”

Democrats in Congress on Monday unveiled legislation aimed at ending excessive use of force by the police and making it easier to identify, track and prosecute police misconduct. The measures were seen as the most expansive intervention into policing that federal lawmakers have proposed in recent memory.

The legislation would curtail protections that shield police officers accused of misconduct from being prosecuted and would set restrictions aimed at barring officers from using deadly force except as a last resort. The fate of the measures was far from certain; they were expected to pass swiftly in the Democratic-led House, but President Trump and Republican lawmakers have yet to signal what measures, if any, they would accept. The legislation under consideration does not contemplate defunding police departments and falls short of what many protesters have demanded.

For his part, Mr. Trump on Monday discarded proposals to remove funds from police departments. “We won’t be defunding our police,” he said. “We won’t be dismantling our police.” His attorney general, William P. Barr, said that it would be wrong to reduce police budgets in part because he felt the country needed more policing to preserve public safety, and warned that the nation would see “chaos” and “more killings” should any major city disband its department.

Former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, “does not believe that police should be defunded,” a campaign spokesman said on Monday, adding that Mr. Biden “supports the urgent need for reform” as well as financial support for community policing programs.

Around the country, city and state leaders were weighing overhauls of their policing policies, aware of the delicate balance of voters’ concerns about crime versus their repulsion at police brutality.

In Albany, New York State lawmakers on Monday began passing a wide-ranging package of bills targeting police misconduct, overcoming deep-seated opposition from law enforcement unions. The measures, many of which have languished for years, include a ban on the use of chokeholds as well as the repeal of a decades-old statute that has effectively hidden the disciplinary records of police officers from public view.

Last week, a City Council budget meeting in Nashville stretched on for more than eight hours, coming to a close well after midnight as residents organized by a coalition of community groups lined up to demand that the police budget be cut.

The idea of removing money from police forces, once largely put forth for years by academics and advocacy groups, appeared to be shifting into the spotlight, as activists and elected officials in cities like Nashville, Portland, Ore., and Denver weighed the possibility.

“This is totally new,” said Stacie Gilmore, City Council member for a largely Latino and African-American district in Denver who had received 2,500 emails in the past three days demanding the city defund the police. “We’re always scrambling to get enough resources. Our Police Department by default serves as social worker, therapist, family counselor, career counselor. We don’t need the police to do that job anymore. It’s not working for communities of color.”

Late last week, after several days of protests, Mayor Ted Wheeler of Portland announced an end to school resource officers, freeing up $1 million to be used elsewhere with community input, according to Tim Becker, a spokesman for the mayor.

Around the country, the calls from activists and other leaders for defunding police departments have taken on different meanings in different places. Most pleas for defunding the police do not signal a wish to end efforts at public safety. Rather, officials say they want to stop spending millions of dollars on certain items for the police, such as military-style equipment. Some proposals seek to trim the number of officers, a prospect that could force a debate over union contracts.

The end goal, advocates say, is to put an end to horrific scenes like the death of Mr. Floyd in Minneapolis.

In that city, council members took a first major step toward dismantling its police force on Sunday when nine of them, a veto-proof majority, pledged to revamp policing. Specifics were uncertain but council members promised to listen to concerns from community groups and cautioned changes would take time.

“We’re reclaiming the conversation of public safety and we’re saying, ‘It doesn’t have to be fear-based, it doesn’t have to be punishment-based,’” said Alondra Cano, a council member.

Other lawmakers and leaders say defunding police departments could have unintended consequences. Some people worry about safety if fewer armed officers are on patrol, especially in summer months when crime rates tend to spike.

Jim Cooper, a Democratic state legislator in California, urged cities to proceed with caution when they consider cutting police budgets.

“You still have bad people out there who do bad things,” said Mr. Cooper, who spent 30 years in law enforcement. “And most of the crime is in underserved neighborhoods, not in SoHo or Beverly Hills.”

After 10 nights of mass protests and several videos documenting police violence in New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio on Sunday vowed to cut an unspecified amount from the New York Police Department’s $6 billion budget and redirect it toward youth and other social programs.

Earlier, Mr. de Blasio had expressed substantial skepticism about the wisdom of cutting police funding, even as he acknowledged that all agencies might face cuts should the federal government fail to come through with more coronavirus relief.

In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti last week agreed to redirect $150 million from the Police Department’s nearly $2 billion budget and other city programs to health and education programs among others. The move came after calls from members of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles and the City Council.

Officials from police unions have pushed back against the idea with sharp rebukes in some cases. In Los Angeles, the union issued a statement saying that a crisis response team should be sent to the mayor “because Eric has apparently lost his damn mind.” Union members warned that spending cuts would lead to more crime.

In Minneapolis, police have used force against black people at a rate at least seven times as often as they have against white people over the past five years, according to the city’s data.

That statistic helps explain why the idea of abolishing the police force makes sense to some African-Americans. Some black people say police departments have not served to protect their communities, but rather to harass and brutalize them. Amanda Brazelton, a resident of Minneapolis’s predominantly black North Side, said she supported using money that now goes to the police to instead create community-led safety efforts.

Ms. Brazelton said negative interactions with the police started when she was 14 and riding in a car that was pulled over. The officers did nothing when her white friends got out, she said. But when she stepped out of the car, the officers pulled weapons on her and yelled.

Now, if there is an issue at her home or she feels in danger, Ms. Brazelton, a 30-year-old caterer, said she would call friends or family before the police.

“As crazy as it seems, it could be something for the better,” Ms. Brazelton said of abolishing the police. “They kill black people.”

There is a difference between defunding the police and abolishing the police, said Arianna Nason, a member of the MPD150 Collective, a coalition of community activists in Minneapolis.

She envisions a city where community watch groups or app-based safety groups could respond to crimes.

The prospect that neighborhood watch groups could stereotype and endanger people of color is also a concern among some people. Ms. Nason said she understood that, but that danger already existed in the current system.

“A lot of it is a leap of faith,” she said. “I want to choose to believe in humanity. I want to choose to believe that this moment feels different because it is different.”

Dionne Searcey and John Eligon reported from Minneapolis, and Farah Stockman from Boston. Reporting was contributed by Maggie Haberman, Thomas Kaplan and Catie Edmondson from Washington; Astead W. Herndon from Houston; Dana Rubinstein and Richard A. Oppel Jr. from New York; Shawn Hubler from Sacramento; Eric Killelea from Minneapolis; and Luis Ferré-Sadurní from Albany, N.Y.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.